This is the story of the first Chinese pioneers, who, unlike us, had little freedom and no rights

When Chinese migrants arrived in Canada, disenfranchised, excluded and isolated, they were pushed to the very corners of society. From those corners, through the generations, Chinese Canadians built our Chinatowns, a small corner of resistance in cities across Canada.

This community, despite the racist legislations of the past, have managed to thrive and grow, to guard these streets that hold fast the stories of those who came before. The long history of Chinese displacement is written in these buildings and handed down to the generations of people who live and visit here.

“You can say Chinatown’s been very resilient because of the long history of racism and exclusion. In fact, Chinatown has had to continually fight for its existence throughout its history.”

Kevin Huang

Today, Chinatown and its community are facing threats on an unprecedented scale, a resurgence in racism, gentrification, degradation and community disengagement. Anti-Asian racism is alive and growing across the country. New research shows over 600 incidents have been reported in Canada since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In March, CityNews reported that an elderly Asian man was assaulted at a convenience store in Vancouver. Then in May, Vancouver’s Chinatown lions were defaced by racist graffiti.

From 2019 to 2020, Vancouver reported that Anti-Asian hate crimes rose by more than 700 per cent. Many of those attacks took place in Chinatown.

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside is the poorest neighbourhood in Canada. It is also ground zero for Canada’s opioid crisis. It also happens to border Vancouver’s historic Chinatown. Fred Kwok runs the Chinese Cultural Centre, and he believes the area’s decline is no accident.

“I believe they are systematically targeting the Chinese Cultural Centre,” said Kwok, “The graffiti on the walls is new, every building here has been covered with graffiti over the years.”

The attacks in Vancouver grew so prolific, the city was labelled as the “Anti-Asian Hate Crime capital of North America.” For Fred, the struggle and threats are daily and he sees no solution. “We have no choice but to see how to face it and digest it,” said Kwok.

To enter Canada’s Chinatowns you must pass through Paifang, a gateway not only to the heart of the Chinese community in Canada, but also to a lost land.

It became a place of memory, a place of nostalgia, where Chinese Canadians would go to feel the spirits of their forebears. For many of the community, it’s a place to engage with heritage, honour their ancestors and seek connections with relatives and friends.

“So maybe that’s why when I see young people fighting for Chinatown, defending it, making sure that it’ll still be here, it’s in a lot of ways also defending those men and their legacy, the fact that they couldn’t have grandchildren be fighting for them,” said Yu.

Canada’s Historic Discrimination

But these threats to Chinatown are nothing new. In fact, it’s very existence is an act of resistance. Segregated and excluded from mainstream society, Canada’s Chinatowns were born out of displacement. The Chinese community were needed for Canada’s development, but were excluded from all other aspects of Canadian life.

Thousands of Chinese migrants helped build Canada’s Transnational Railway (CTR). When the Railway was finally complete in 1885, Canada’s white settler government wrote into law the Head Tax, a punitive tax on Chinese migrants wanting to enter Canada. It signalled the beginning of a decades-long anti-Chinese immigration policy that would last until the 1960s. These racist immigration policies pushed Chinese migrants into the areas we know today as Chinatown.

Vancouver’s Chinatown was nearly destroyed in the Race Riots of 1907, when 10,000 white workers wreaked havoc across the neighbourhood for three days. The 1907 riots were a potent expression of the anti-Asian racism that was simmering in cities across Canada.

Due to the legislated discrimination and exclusion, Chinese migrants arriving in Chinatown developed strong community bonds and relied on family associations for support. They played an important role in shaping Chinatown through the 20th century. Many of the oldest historical buildings belong to these family associations.

Issues of Gentrification

As the societal make-up of Canada’s Chinatowns shifts, the community must also adapt and adjust. Most notably in the 1950s, the struggle became nearly insurmountable in Toronto. Two thirds of the city’s Chinatown was razed to make way for City Hall, forcing much of the community to move.

Yet, despite this discrimination businesses and organizations in Toronto’s Chinatown thrived. The Chinese community depended on each other to uphold their traditions, honour their history and invest in the future of Chinatown.

Standing up to government and resisting private development in Chinatown is something that the community has a long history of.

For instance, in 2015, the fight to stop rampant development in Vancouver’s Chinatown reached its climax when plans were announced for a 12-story tower at 105 Keefer Street in Vancouver. The community, including many young activists, mobilized to stop the plans. Their message? Enough is enough.

“Gentrification is the process of urban renewal or urban displacement, often resulting in typically white upper class businesses and residents taking over the spaces of neighborhoods that used to be for racialized and low income folks. And that’s happening in Chinatown.”

Kimberley Wong

The development was slated but the property is still up for contestation. “I think 105 Keefer, had it been built, would’ve symbolized the end of Chinatown as we know it,” said Kimberley Wong, “The end of the things that we love about Chinatown. The legacy businesses where you can buy things like barbecue meats and the end of fishmongers, the end of dim sum restaurants here, the end of Hong Kong bakeries and cafes.”

The issue of gentrification is not just felt in Vancouver. In the end, the issue of gentrification comes down to cultural heritage, a concept whose value is hard to quantify in dollars.

“What more to make them understand this is so important? Culture is the future for the next generation to understand, to respect one another. Without a culture, there is no respect. Without respect, there’s no honour.”

Jimmy Chan

Societal and Economic Pressures

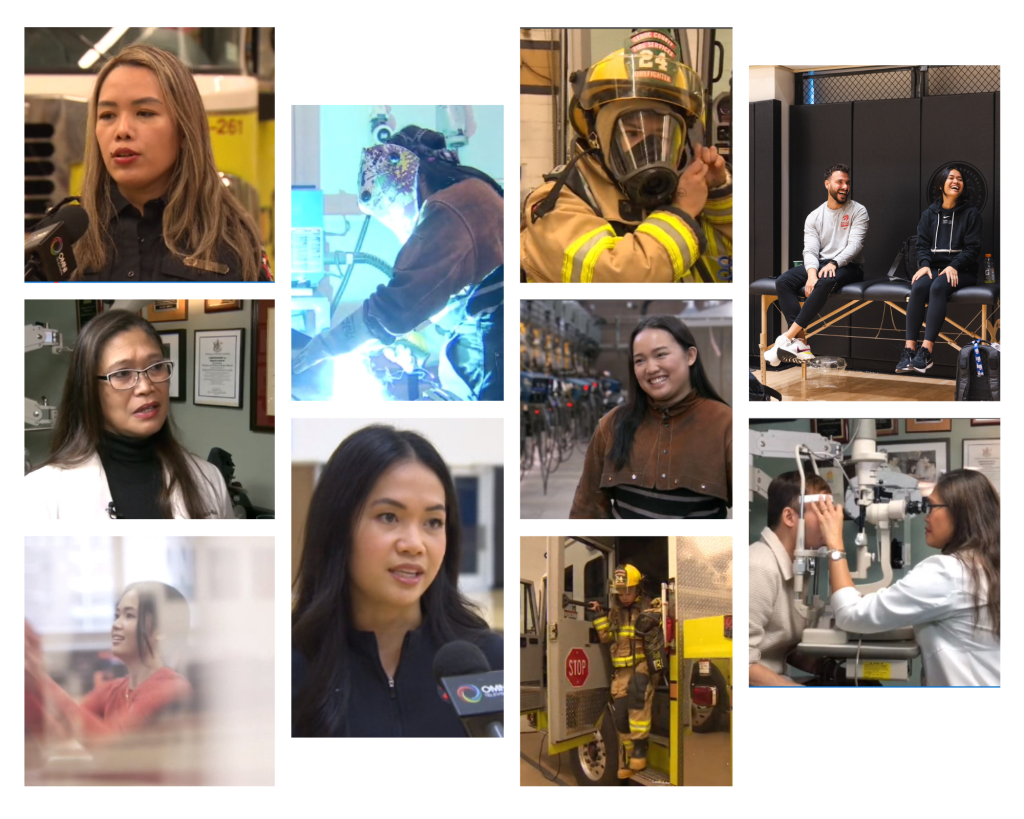

In Vancouver’s Chinatown, young entrepreneurs are finding new ways to do business by fusing tradition with innovation. One of them is William Liu, a young businessman who gave up a promising music career to come back to Vancouver’s Chinatown, and take over the family dumpling business. Running the family business has been a challenge, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, but he doesn’t regret his decision.

“I’m just so proud of myself to be able to continue the legacy along with others. It’s an amazing feeling,” said Liu.

William is part of a vanguard of culinary entrepreneurs opening new businesses in Chinatown, many are fusing traditional ingredients with modern recipes and contemporary design.

“If you think about the history of Chinatown, [the food] really was sort of the magnet that brought people down from all different kind of background.”

Carol Lee

On the other hand, set against this renaissance is the idea that traditional Chinese businesses are low status. Younger generations feel a familial and societal pressure to pursue professional occupations away from the family business. “They don’t want their children to have to do that to survive,” said Kimberley Wong.

Much of the community are worried about the future of Chinatown. Fearful about losing a part of their history and ancestors.

“I think that many of us could see that over time, without some intervention, that maybe Chinatown would just eventually disappear. I think when you’re faced with the idea of losing something, that’s when you reflect […] I think for a lot of us, Chinatown meant a lot,” said Lee.

One Toronto photographer has seen that decline with his own eyes. For the past 10 years, Morris Lum, has been photographing Canada’s Chinatowns, immortalizing the buildings and streets through photography, to ensure that whatever happens, their memory will live on through the ages.

Morris has travelled the country, documenting the differences and changes in Canada’s Chinatowns. “When I started the project I realized that Vancouver’s Chinatown was changing quite quickly. A lot of the older spaces were being demolished and

being turned into self story condominiums,” he recalled.

Chinatown’s Future

The survival of Chinatown depends on its continuing relevance, especially to the next generation. But there are signs of hope. In Vancouver, campaigners have applied for UNESCO world heritage status. As well, Montreal’s Chinatown, threatened by developers, was granted heritage status in January 2022.

Most of the activists and supporters are the younger generations, which Sonny Wong thinks is vital to the future of Chinatowns across Canada. “I think a lot of the energy in, and around, Chinatowns today has come from the younger generation. It’s come from the younger generation who suddenly have seen Chinatown slip away and they don’t want to lose that part of their heritage,” said Sonny Wong.

Not a blank canvas for real estate developers, but a vibrant community filled with innovative businesses and new ideas. As memories of Canada’s exclusionary and discriminatory policies fade, remembering the significance and importance of these streets becomes more important than ever. Chinatowns are upholding its heritage and history, yet thinking of its future and allowing for new traditions to be implemented.

To the Chinese community, Chinatown is a historical delicacy engraved with decades of hard work and honour.

“Chinatown is a symbol, as a place of refuge, but it’s also a place of hope. Throughout its history, for those who have been vulnerable, marginalized, it’s an inclusive place. […] It’s also a place, that despite this constant idea that it’s going to die, that it’s dying, that people keep rallying to it,” said Yu, “Each generation, you could say, has rallied to make sure that it doesn’t disappear, that it doesn’t die. So, in that sense, the resilience is real.”